My dad used to have a trunk in the shed where he hid his collection of risqué books. Naturally, aged 12, my best friend and I spent hours in that shed, seeking out ‘the dirty bits’ of each book to read aloud to each other.

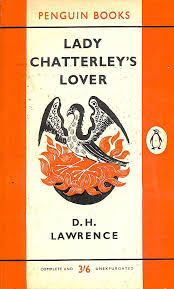

The orange and white cover of Lady Chatterley’s Lover wasn’t promising but the title seduced us. It told the story of an affair between Lady Chatterley and her gamekeeper. Romantic and passionate it was brimming with dirty bits. The f-word arose 30 times; the c-word cropped up 14 times and a glorious selection of other filthy words and sexual suggestions danced before our eyes.

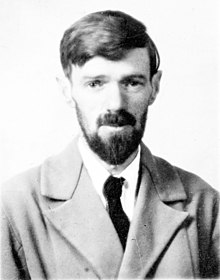

Lady Chatterley’s Lover was written by D. H. Lawrence in 1928. Immediately declared obscene, it was published abroad, in small private editions, and often with the lewdest sections cut out.

In 1935, London publisher Allen Lane had a revolutionary idea. He wanted to sell serious and affordable literature to the working class. He founded Penguin Books, publishing high quality paperbacks for sixpence each.

After the War, people started to challenge the British Establishment. We’d seen Elvis gyrating; our playwrights had become ‘Angry Young Men’ and the seeds of later rebellion were sown.

In 1960 Penguin Books published the full version of Lady Chatterley’s Lover as a paperback costing 3/6d.

A public prosecution ensued accusing Penguin of publishing obscenity. The trial was held at the Central Criminal Court known as the Old Bailey.

This was not a clear cut case. The Obscene Publications Bill of 1959 had included a let-out clause for certain publications with serious ‘literary merit’ that justified their ‘obscene’ content. Penguin Books had to prove that this was the case here.

The main prosecutor, Mervyn Griffith-Jones accepted that D.H. Lawrence who had died 30 years previously, was a writer of merit. But he was disturbed by the flagrant adultery described. What made it beyond redemption was the affair between an upper class lady and a common gamekeeper.

He asked the court: “Would you approve of your young sons, young daughters—because girls can read as well as boys—reading this book? Is it a book you would have lying around your own house? Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?”

The British public read this quote and fell about laughing. Your servants?

The defence brought out a string of witnesses that included academics, women, and a bishop who argued coherently that the book should be published.

On 2 November 1960, the Judge ruled that Penguin books were not guilty.

In Britain we said: Goodbye old order. Hello Permissive Society.

By the end of the day, 200,000 copies of Lady Chatterley’s Lover were sold to men, women, girls, boys, servants – and my dad.